This post is not what I thought it would end up being about. I had plans, but it seems fate, and the dark corners of my brain, had a different path set out for me. You see after I wrapped up my last post on PIC93 I had LZSS compression on my mind, and thought maybe it was a good time to dive into LZSS. Specifically how it was used to compress the executable files for many MicroProse titles in the early 1990’s. I wasn’t even planning to blog about it at this time, it was only meant as a distraction for a little while. Then it happened…

Ever since I discovered that the MicroProse executables were compressed using the LZSS algorithm. I’ve wanted to dig into this algorithm some more. Time to dust off my data compression book from ye olde bookshelf of obsolete books and see what we can learn about the Lempel–Ziv–Storer–Szymanski (LZSS) compression algorithm. In this post we will concentrate on decompression, as that is the part of most interest to me at the moment.

1977 – Lempel-Ziv

We can’t really start talking about LZSS without talking about LZ77 first. Like most (lossless) compression algorithms of the time, and even today, they are built upon the early works of Abraham Lempel and Jacob Ziv. LZ77 is a sliding-window dictionary based compression algorithm. That is to say that the dictionary of replacement patterns slides along with the position in the decoded stream, instead of being fixed or dynamically built (like LZ78 and LZW). This approach has an interesting side-effect that allows for RLE (Run Length Encoding) like behaviour to be encoded directly in the compressed stream. This is accomplished by specifying a length value that exceeds the distance value. Unlike RLE, the repeated sequence copied forward need not be that of a single token. The simplest example would be to say, go back 1 byte, and copy 100 bytes. This would cause the last written byte to be duplicated 100 more times. But it need not be a byte, it could be of any arbitrary length. Imagine a 16 bit word value, where the upper and lower bytes do not share the same value. This can be replicated just as easily with LZ77 with Go back 2 bytes, copy 16 times, to make 8 copies of the previous word.

1982 – Storer-Szymanski

James Storer and Thomas Szymanski first published their paper describing what we now call LZSS in 1982. Not unlike LZW compression which we covered in a previous post, which improved upon LZ78, LZSS improves upon LZ77. The main improvements that Storer-Szymanski made to LZ77 is the use of a flag bit to distinguish between literal data, or a replacement pattern, also that replacement patterns are omitted if the replacement reference code would be larger than the original.

Implementing a LZSS decompressor is fairly straight forward, and can be quite fast and compact, as the dictionary is the decompressed code itself, and the replacement codes are just negative offsets into the decoded datastream itself. The only challenge is performing non-byte aligned access to the stream, as well as reading back values that are not exactly a multiple of a byte. This same challenge exists for many other LZxx based algorithms, including LZW which we previously covered.

The basic implementation of LZSS

The basic implementation code below is transcribed from my data compression book pictured above by Mark Nelson and Jean-Loup Gailly. The code is for illustration purposes, and unapologetically makes no effort for optimization, despite that it is still quite compact.

void ExpandFile(BIT_FILE *input, FILE *output, int argc, char* argv[]) {

int i;

int current_position;

int c;

int match_length;

int match_position;

current_position = 1;

for( ; ; ) {

if(InputBit(input)) {

c = InputBits(input, 8);

putc(c, output);

window[current_position] = c;

current_position = MOD_WINDOW(current_position + 1);

} else {

match_position = InputBits(input, INDEX_BIT_COUNT);

if(match_position == END_OF_STREAM)

break;

match_length = InputBits(input, LENGTH_BIT_COUNT);

match_length += BREAK_EVEN;

for(i=0; i <= match_length; i++) {

c = window[MOD_WINDOW(match_position + i)];

putc(c, output);

window[curent_position] = c;

current_position = MOD_WINDOW(current_position + 1);

}

}

}

}

The fact that we have non-byte sized symbols and boundaries is one of the major pitfalls to this implementation, as the decompression code needs to do a lot of bit shifting of the data. On some architectures this can be incredibly inefficient.

1988 – Haruhiko Okumura

In 1988 Haruhiko Okumura published his implementation of the LZSS algorithm, with some key modifications, to a BBS network in Japan. (republished in 1989 to the public domain, and archived here) Okumara’s implementation is probably considered the de-facto reference implementation for LZSS, and can even be found in Apple’s MacOS source. Most LZSS implementations are based off of Okumura’s 1988 code.

In the spring of 1988, I wrote a very simple data compression program named LZSS in C language, and uploaded it to the Science SIG (forum) of PC-VAN, Japan’s biggest personal computer network.

That program was based on Storer and Szymanski’s slightly modified version of one of Lempel and Ziv’s algorithms. Despite its simplicity, for most files its compression outperformed the archivers then widely used.

Haruhiko Okumura

The major improvement that Okumara made to LZSS over the basic implementation, was to make everything fall on byte boundaries, this greatly reduces the amount of data that needs to be shifted. To do so, he packs 8 flag bits into a single byte, and once all 8 bits have been consumed, the next flag byte is read. These flag bytes are inter-mingled with the data literals, and reference pointers. So maintaining the proper sequence between the compressor and decompressor is critical.

The Okumura Implementation of LZSS

void Decode(void) /* Just the reverse of Encode(). */

{

int i, j, k, r, c;

unsigned int flags;

for (i = 0; i < N - F; i++) text_buf[i] = ' ';

r = N - F; flags = 0;

for ( ; ; ) {

if (((flags >>= 1) & 256) == 0) {

if ((c = getc(infile)) == EOF) break;

flags = c | 0xff00; /* uses higher byte cleverly */

} /* to count eight */

if (flags & 1) {

if ((c = getc(infile)) == EOF) break;

putc(c, outfile); text_buf[r++] = c; r &= (N - 1);

} else {

if ((i = getc(infile)) == EOF) break;

if ((j = getc(infile)) == EOF) break;

i |= ((j & 0xf0) << 4); j = (j & 0x0f) + THRESHOLD;

for (k = 0; k <= j; k++) {

c = text_buf[(i + k) & (N - 1)];

putc(c, outfile); text_buf[r++] = c; r &= (N - 1);

}

}

}

}

Despite not being the most readable bit of code with liberal use of single letter variable names. there is a certain elegance to the code.

1989 – Fabrice Bellard

In 1989 then 17 year old Fabrice Bellard wrote LZEXE, and distributed it on a few BBS’s, which became wildly popular very quickly. This including landing in the lap of MicroProse who used the program to compress their game binaries, starting in the early 90’s, and ultimately serving as the genesis for this post. The LZEXE decompression code was tiny, occupying only 330 bytes, and it was fast, making it very attractive to anyone looking to squeeze a few more bytes onto a floppy disk. The algorithm used is based on the implementation that was first published by Okumura, like most LZSS implementations. Despite being based upon the Okumura code, it is not a complete replication, and makes a few key changes and improvements.

One of the first changes is that Bellard made was to change the flags from a byte to a word, so in his implementation there are 16 bit control words interspersed in the compressed data stream. Another key change is that he offered up an additional replacement pointer size, allowing for more efficient packing for short distances and lengths. He accomplished this while still maintaining the critical byte alignment by cleverly using more flag bits to control what the next token will be. Bellard also added a terminating sequence, and a few other control sequences into the stream, instead of simply relying on when the data runs out.

The Bellard Implemtation of LZSS

I don’t have access to the official LZEXE code, as far as I know it has never been published publicly. Though it has been reversed and published by others. Below is the decompression routine from the open-source project unlzexe, and being in C is somewhat easier to grasp for most, I think. If you’re interested in the original ASM, there is a great breakdown here, along with a fascinating discussion of the underpinnings of the algorithms implementation.

int unpack(FILE *ifile,FILE *ofile){

int len;

WORD span;

long fpos;

bitstream bits;

static BYTE data[0x4500], *p=data;

fpos=((long)ihead[0x0b]-(long)inf[4]+(long)ihead[4])<<4;

fseek(ifile,fpos,SEEK_SET);

fpos=(long)ohead[4]<<4;

fseek(ofile,fpos,SEEK_SET);

initbits(&bits,ifile);

printf(" unpacking. ");

for(;;){

if(ferror(ifile)) {printf("\nread error\n"); return(FAILURE); }

if(ferror(ofile)) {printf("\nwrite error\n"); return(FAILURE); }

if(p-data>0x4000){

fwrite(data,sizeof data[0],0x2000,ofile);

p-=0x2000;

memmove(data,data+0x2000,p-data); /* v0.9 */

putchar('.');

}

if(getbit(&bits)) {

*p++=(BYTE)getc(ifile); /* v0.9 */

continue;

}

if(!getbit(&bits)) {

len=getbit(&bits)<<1;

len |= getbit(&bits);

len += 2;

span=(BYTE)getc(ifile) | 0xff00; /* v0.9 */

} else {

span=(BYTE)getc(ifile);

len=(BYTE)getc(ifile); /* v0.9 */

span |= ((len & ~0x07)<<5) | 0xe000;

len = (len & 0x07)+2;

if (len==2) {

len=(BYTE)getc(ifile); /* v0.9 */

if(len==0)

break; /* end mark of compressed load module */

if(len==1)

continue; /* segment change */

else

len++;

}

}

for( ;len>0;len--,p++){

*p=*(p+(int16_t)span); /* v0.9 */

}

}

if(p!=data)

fwrite(data,sizeof data[0],p-data,ofile);

loadsize=ftell(ofile)-fpos;

printf("end\n");

return(SUCCESS);

}

One thing to note about Bellard’s implementation, and that is it was written specifically for DOS in a 16 bit environment, as such the coding had provisions for segment change that is not needed in our modern 32 and 64 bit world with linear address space. As you can see in the code above, that sequence simply acts as a NOP (No Operation).

Lightning strikes

And that’s when it hit me… I swear I had not meant to go down this path, but here we are. For those following along, do you remember in my last post thinking that the 55 55 sequence was some sort of magic data marker? We of course discovered that it was not after looking at a few more files. It is however 16 bits in length, and the Bellard implementation uses a 16 bit control word… Bueller? Bueller?

Could it be that those 16 bits are the control word of flag bits, and the compression used in the PIC93 format is the Bellard implementation? We know already that MicroProse was at least partially familiar with it, they were using his program to compress their binaries. I think it’s a fair assumption that they were keenly aware of LZSS, and the Bellard implementation. So the 55 55 looks like it could be a control word of flag bits, let’s walk the sequence for a few bytes to see if things make sense.

55 55 (b=16) flags load flags: 0x5555

00 (b=15) f=1 literal byte flags: 0x2AAA

FF F8 FC (b=13) f=0,1 copy replicate (long) flags: 0x0AAA

FF F8 FC (b=11) f=0,1 copy replicate (long) flags: 0x02AA

FF F8 FC (b=9) f=0,1 copy replicate (long) flags: 0x00AA

FF F8 FC (b=7) f=0,1 copy replicate (long) flags: 0x002A

FF F8 FC (b=5) f=0,1 copy replicate (long) flags: 0x000A

FF F8 FC (b=3) f=0,1 copy replicate (long) flags: 0x0002

FF F8 FC (b=1) f=0,1 copy replicate (long) flags: 0x0000

DB 56 (b=16) f=0 flags reload flags: 0x56DBWell that looks promising! I could walk it further, but not up for the pain today. Instead, let’s write up a LZSS decompressor, and add it to our PIC93 code. That sounds like more fun to me!

Implementing the Bellard-LZSS decompressor

Note: I’ve stripped out all of the error checking at the reads and writes to keep things more readable.

int get_bit(bit_buf_t *src) {

// reload our working buffer when empty

// order here is important, to maintain sync

uint8_t bit = src->buffer & 0x0001;

src->count--;

src->buffer >>= 1;

if(0 == src->count) {

memcpy(&src->buffer, &src->stream->data[src->stream->pos], 2);

src->bytes->pos += 2;

src->count = 16;

}

return bit;

}

void lzss_decompress(memstream_buf_t *dst, memstream_buf_t *src) {

bit_buf_t control_word;

int16_t offset = 0;

int16_t length = 0;

// initialize the bit buffer, and preload with first control word

init_bit_buf(&control_word, src);

while (1) {

// test if the next byte is a literal

if (0 != get_bit(&control_word)) { // copy

dst->data[dst->pos++] = src->data[src->pos++];

continue;

}

// test if pointer is short or long type

if (0 == get_bit(&control_word)) { // short

length = get_bit(&control_word) << 1;

length |= get_bit(&control_word);

length += 2;

offset = src->data[src->pos++] | (0xFF00);

} else { // long

offset = src->data[src->pos++];

length = src->data[src->pos++];

offset |= ((length & ~0x0007) << 5) | 0xe000;

length = (length & 0x007) + 2;

if(2 == length) { // long long or control

length = src->data[src->pos++];

if(0 == length) { /* end mark for compressed stream */

// this is the end of the road

break;

}

if(1 == length) { /* segment change */

// this is a NOP for us

continue;

}

length++;

}

}

while(length--) { // expand

dst->data[dst->pos] = dst->data[offset + dst->pos];

dst->pos++;

}

}

}

The above is fundamentally the same as the unlzexe code, except I removed the window buffer stuff, as we have everything in memory, so the output memory buffer can double as the window buffer. Now the question is… will it decompress?

Explorer for MicroProse PIC93 Files

Analyzing: 'LABS.PIC' File Size: 6644 bytes

Image: 640x400

Pos: 56

Block 0 Length: 2376

src(2376/2376)

dst(32000/32000)

Pos: 2434

Block 1 Length: 1888

src(1887/1888)

dst(32000/32000)

Pos: 4324

Block 2 Length: 1888

src(1887/1888)

dst(32000/32000)

Pos: 6214

Block 3 Length: 428

src(427/428)

dst(32000/32000)

Pos: 6644

DoneHoly crap!!! It seems to have worked. Full plane decompressions, no errors. Wow. (full disclosure, it took a couple of tries because of silly coding errors, but I saved you the pain of that). Looks like some of the reads left a byte behind, but seems to be only when the an odd number of bytes was consumed, perhaps the blocks are padded out to land on a 16 bit word boundary. Makes sense actually, as the block header starts off with a 16 bit value, and it’s best if that is word-aligned.

Now we have 4 planes of bit packed data, all that’s left to do is recombine them. I’ll start by trying little endian order for the bits in the planes, as was the case with other files. For the bit order in the reconstituted nibble, I’m going to follow the arrangement I found on this page for the PC-9801’s graphics system. I’ll go on the assumption that the plane order in the file is in the same order A0-A3 shown in the PC-9801 graphics system detailed description. Below is the basic re-assembly and rendering for the PPM format we’ve been using for testing.

fprintf(fo, "P6\t%d\t%d\t%d\n", hdr.width, hdr.height, 255);

for(int y = 0; y < (hdr.height); y++) {

for(int x = 0; x < (hdr.width / 8); x++) { // 8 pixels per byte

uint32_t pos = (y * (hdr.width / 8)) + x;

uint8_t p0 = planes[0][pos];

uint8_t p1 = planes[1][pos];

uint8_t p2 = planes[2][pos];

uint8_t p3 = planes[3][pos];

pos++;

for(int b = 0; b < 8; b++) {

uint8_t px = 0;

px |= p3 & 0x01; px <<= 1;

px |= p2 & 0x01; px <<= 1;

px |= p1 & 0x01; px <<= 1;

px |= p0 & 0x01; // last bit is in-place, no shift needed

p0 >>= 1; p1 >>= 1; p2 >>= 1; p3 >>= 1; // shift in the next pixel

// write out the pixel, in RGB from the palette

int nr = fwrite(&hdr.pal[px], 3, 1, fo);

}

}

}

Note that since we want P3 in the most significant position, it is shifted in first. With that done, let’s see how we did.

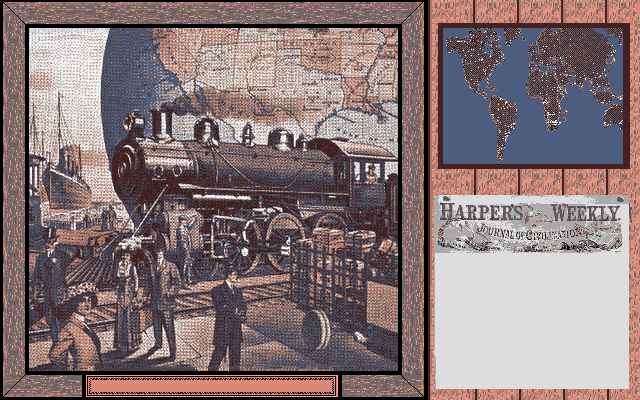

Neat effect, but not what we’re looking for here. The bit’s must be ordered MSb-LSb in the planes. Meaning we also need to reverse the order in which we shift in the bits. But the colours look good, so our plane ordering must be correct.

for(int b = 0; b < 8; b++) {

uint8_t px = 0;

px |= p0 & 0x80; px >>= 1;

px |= p1 & 0x80; px >>= 1;

px |= p2 & 0x80; px >>= 1;

px |= p3 & 0x80; px >>= 4; // final shift down to the lower nibble

p0 <<= 1; p1 <<= 1; p2 <<= 1; p3 <<= 1; // shift in the next pixel

int nr = fwrite(&hdr.pal[px], 3, 1, fo);

}

That should fix the problem we saw in our first attempt, let’s try now and see what we get.

Bingo! For good measure, let’s try a few more.

I’d call that a success. I hadn’t planned on decoding the PIC93 images today, but here we are with that item crossed off the list of future projects. I have to say, MicroProse did some really beautiful work with the artwork on Railroad Tycoon Deluxe.

With that done, I think this is a good place to wrap up. We were able to confirm that the MicroProse PIC file format used with Railroad Tycoon Deluxe, or as I’ve been calling it PIC93, is indeed using LZSS compression. More specifically it is using the Bellard implementation that was used with LZEXE. Since we’ve made it this far, I guess in my next post will be to tackle writing a compressor for this version of LZSS. I imagine that will be a more difficult task than the decompression, should be interesting.

This post is part of a series of posts surrounding my reverse engineering efforts of the PIC file format that MicroProse used with their games. Specifically F-15 Strike Eagle II (Though I plan to trace the format through other titles to see if and how it changes). To read my other posts on this topic you can use this link to my archive page for the PIC File Format which will contain all my posts to date on the subject.

Leave a reply to David Cancel reply