This is actually a format variant I did a while back, but never got around to writing about it. In this case it’s a .BIN image file from SSI’s Western Front. I’ve decided to include it with their .IMG format as it is raw image data just like the IMG format is, with only a slight difference in how the data is encoded. Also I felt .BIN was a bit too generic to be considered it’s own unique type, this is more of an alias extension. So let’s dig into it and see what the differences are.

What to expect

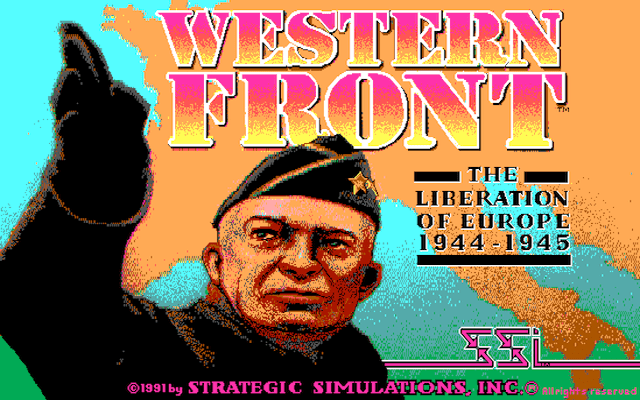

First thing is to see what we expect the image looks like. That always helps us down the road. Thankfully we can see what we believe is the output for this file in game, and in screenshots scraped from the web.

Now that we know what we’re looking at, let’s see how this translates to the data in the file itself.

First look

File: WESTFRNT.BIN [112000 bytes]

Offset x0 x1 x2 x3 x4 x5 x6 x7 x8 x9 xA xB xC xD xE xF Decoded Text

0000000x: FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0000001x: FF FF FF FF FF F7 FF DF FF FF FF FF FD FF FF FF · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0000002x: FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0000003x: FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0000004x: FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0000005x: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0000006x: 00 00 00 00 00 1F FF F0 00 00 00 00 17 FF FF FF · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0000007x: FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·First thing that jumps out is the data is obviously not compressed. Beyond that I would say given we see a lot of FF and 00‘s this data is likely planar in nature, given the colouring we seen in the rendered image (we don’t see huge swaths of white or black). Next thing of note is the size, this actually threw me for a moment as it is an oddball size, we do know the game is EGA based, so that limits us in our resolution choices. A 320×200 image would occupy 64,000 bytes (32,000 if packed). At 640×200 image would double that to 128,000 bytes (64,000 packed) packed. This is neither of those. Maybe it’s VGA after all and 640×480? Nope, that would be 307,200 bytes (153,600 packed). Time to consult our trusty online video modes reference to see what other options there are, assuming it’s not a non-standard mode. I had forgotten about EGA’s 640×350 16 colour mode, let’s see if that works… 224,000 bytes which would be 112,000 bytes packed. The shoe fits! So now we know our resolution and that it’s likely planar data, let’s try to decode it. My first guess is that this is the same format as the .IMG format we’ve already seen form SSI. So let’s give that a shot.

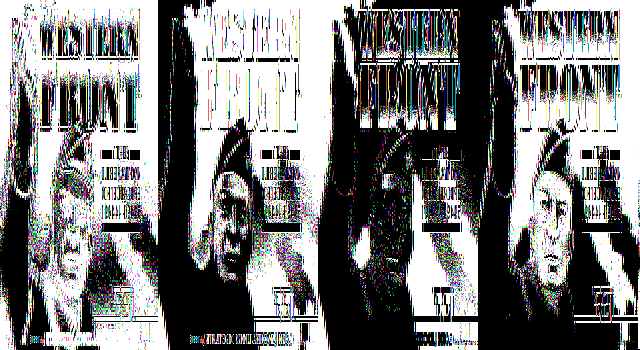

Well that’s clearly not correct. We do see some elements of the reference image, but looks like bad sync on a television from back in the ’70’s and ’80’s. Clearly this is not exactly the same format as the .IMG file we looked at previously. Maybe it’s not planar data? Let’s take a look at it as a RAW image.

Okay so it is obviously planar. From the fact that we see only the 4 planes horizontally, and they occupy the entire height of the image, it looks like the planes are encoded on a line-by-line basis instead of as the whole image like the .IMG format was. If it was image-planar then I would expect to see the image tiled both horizontally, and vertically. This is because the line data is still 1/4 the width, so you get four lines of image data per line of rendered image if you leave the original dimensions the same. and then vertically you get the 4 planes. For reference I’ll add an image below to show what that would look like, having the benefit of writing this up after the image had been decoded. We’d have to make the image 1/4 the width to see only the 4 planes, stacked vertically.

We saw this two-way tiling before when we did the .IMG decoding, but it was harder to spot due to the nature of the image. But looking back now, knowing what to look for, it is quite obvious. Now we know the dimensions, and data arrangement, time to write some code to put it together into a proper image.

Rendering the BIN file

De-planing the .BIN format is pretty straight forward, it’s a bit like a cross between the planar decoding and de-interlacing, both of which we had to do for the .IMG format. We just need to grab a full lines worth of data, and then divide it into 4 to get at each of our planes. Repeat this process for each line of the image.

void ipln2lin(memstream_buf_t *dst, memstream_buf_t *src,

uint16_t width, uint16_t height) {

int step = width / 2; // bytes per line

int ofs2 = step / 2; // 1/2

int ofs1 = ofs2 / 2; // 1/4

int ofs3 = ofs1 + ofs2; // 3/4

int base = 0;

for(int y = 0; y < height; y++) {

for(int x = 0; x < (width / 8); x++) {

uint8_t p0 = src->data[base + x]; // grab the bytes from the 4 planes

uint8_t p1 = src->data[base + ofs1 + x];

uint8_t p2 = src->data[base + ofs2 + x];

uint8_t p3 = src->data[base + ofs3 + x];

for(int b = 0; b < 8; b++) { // 8 pixels packed per byte

uint8_t px = 0;

px |= p0 & 0x80; px >>= 1;

px |= p1 & 0x80; px >>= 1;

px |= p2 & 0x80; px >>= 1;

px |= p3 & 0x80; px >>= 4; // final shift

if(dst->pos < dst->len) dst->data[dst->pos++] = px;

p0 <<= 1; p1 <<= 1; p2 <<= 1; p3 <<= 1; // shift in the next pixel

}

}

base += step;

}

}

With the code written, let’s see how we did.

Looks like we nailed the image decoding, but the game appears to be using a non-standard palette. I did try different ordering of the planes but that didn’t make it any better, it’s clear that some of the base colours in the reference image are just not there. If we want to get a correct rendering we will need to determine the palette. We could cheat of course, and pull the palette from the reference image, but where’s the fun in that?

Finding the palette

As this is EGA, which does not really have a programmable palette, and we have a static image, this should be pretty straight forward. We know the data arrangement, so all we need to do is create a BIN file that uses all 16 possible colours. As the planes are encoded on a line-by-line basis we can easily create an image of 16 vertical bars for each of the colours by generating one line of data, and then repeating it for the rest of the image.

Technically EGA does have a programmable palette, only that it is 6 bits, with 2 bits of data for each colour, resulting in a total of 64 possible colours. Though only 16 can be used at any given time. Each of the 16 colours can be mapped to any of the 64 possible colours by programming a colour index value. The bitwise data arrangement is simply xxRGBrgb where the bits are simply pulled from the 8-bit palette index value.

Let’s throw together a simple program to generate the palette discovery image.

int main(void) {

FILE *fp = fopen("PAL.BIN", "wb");

uint8_t buf[WIDTH / 2]; // bytes per line (4 bits per pixel)

// generate a single line of paletted data

int i=0;

int mask = 1;

for(int plane = 0; plane < 4; plane++) {

for(int colour = 0; colour < 16; colour++) {

// bytes per line / planes / colours

for(int byte = 0; byte < (WIDTH / 2 / 4 / 16); byte++) {

// each bit of the colour represents either a byte of all 0's or 1's

buf[i++] = (0 != (colour & mask))?0xff:0;

}

}

mask <<= 1;

}

// repeat the line for the entire height of the image

for(int y = 0; y < HEIGHT; y++) {

fwrite(buf, WIDTH / 2, 1, fp);

}

fclose(fp);

}

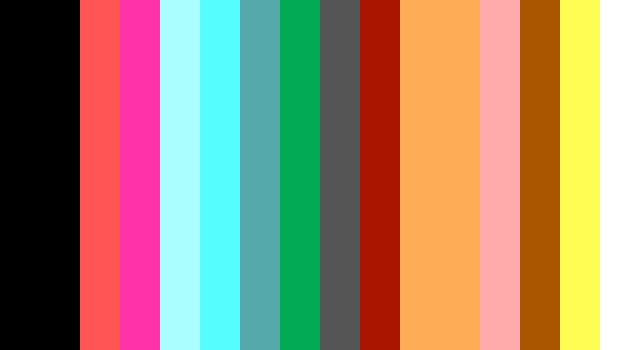

Running the program we see that we do get a .BIN with the correct size of 112,000 bytes But the proof is in the output, let’s run it through our decoder and see what we get.

Perfect! Now to replace “WESTFRNT.BIN” with our “PAL.BIN” and capture what the game produces.

Great, we now have our palette. All we need to do is extract it from the image and map it back to the EGA palette, which is easy, and then re-render our original BIN file with the new palette.

And there you have it, a properly decoded and rendered image. Now all that’s left is to go the other way. Getting the palette was purely for aesthetics of the extracted file, it is not encoded in the BIN file, so when we encode any custom graphics they will use the palette above, as that is hard-coded into the game engine. (in theory the game engine could be modified to use different values by editing the executable)

Writing the BIN encoder

Encoding an image back into this .BIN format is equally as simple. Basically just the reverse of decoding. Decompose a pixel into 4 bits, and store each of those bits in a byte for each of the planes. After 8 pixels, the bytes should be full, write them out to a line buffer and start over until we reach the end of a single line. Then write out the lines-worth of data, and start over with the next line.

void lin2ipln(memstream_buf_t *dst, memstream_buf_t *src,

uint16_t width, uint16_t height) {

int step = width / 2; // bytes per line

int ofs2 = step / 2; // 1/2

int ofs1 = ofs2 / 2; // 1/4

int ofs3 = ofs1 + ofs2; // 3/4

int base = 0;

for(int y = 0; y < height; y++) {

for(int x = 0; x< (width / 8); x++) {

uint8_t p0 = 0;

uint8_t p1 = 0;

uint8_t p2 = 0;

uint8_t p3 = 0;

for(int b = 0; b < 8; b++) { // 8 pixels packed per byte

p0 <<= 1; p1 <<= 1; p2 <<= 1; p3 <<= 1; // make room for the next pixel

uint8_t px = 0;

if(src->pos < src->len) px = src->data[src->pos++];

p0 |= px & 0x01; px >>= 1;

p1 |= px & 0x01; px >>= 1;

p2 |= px & 0x01; px >>= 1;

p3 |= px & 0x01; px >>= 1; // final shift

}

// write it to the output

dst->data[base + x] = p0;

dst->data[base + ofs1 + x] = p1;

dst->data[base + ofs2 + x] = p2;

dst->data[base + ofs3 + x] = p3;

}

base += step;

}

}

With that done, testing and validation should be pretty easy. If we take our decoded image, and re-encode it, we should end up with something that is exact to our original .BIN image.

% bmp2bin WF.BMP

BMP to SSI-BIN IMG image converter

Loading BMP File: 'WF.BMP'

Resolution: 640 x 350

Creating BIN File: 'WF.BIN'

Done

% ls -al WF.BIN

-rw-r--r-- 112000 12 Sep 14:58 WF.BINThat’s a good sign, no complaints from the encoder, and our output size is correct. Now to see how it compares to the original.

% md5 WESTFRNT.BIN WF.BIN

MD5 (WESTFRNT.BIN) = 4a6a509be2a1d62ae9421792a0deaca9

MD5 (WF.BIN) = 4a6a509be2a1d62ae9421792a0deaca9A complete success! We now have the ability to both decode and encode the image. With that I think that’s a wrap for this format.

Due to the similarities to the .IMG format I consider this to be a variant of it, with .BIN just being an alias. As such I’ve added the decoding and encoding code to the SSI-IMG github repo. For decoding a “b” suffix has been added, and for encoding there is a stand-alone tool. In addition the extracted palette is in the decoding code, but commented out, for anyone interested in working with the palette. I decided not to add custom palette code to the tool at this time, instead you can simply comment and un-comment the desired palettes and rebuild. If we start to see more titles using this format we can look at adding proper code for palette management.

Leave a comment